How to be Successful as a New Manager

Whether you are a new to the role, new to a company or domain, or you’re taking over a new team, you deal with various unknowns. This makes it tricky to know if you are focussing on the right problems early on.

I was a new manager at one point in my 20-year career, and subsequently found myself in several situations leading new teams, exploring new business domains, and companies. I had the good fortune to work with really smart engineers and leaders, as well as a chance to make my fair share mistakes — each of which taught me valuable lessons.

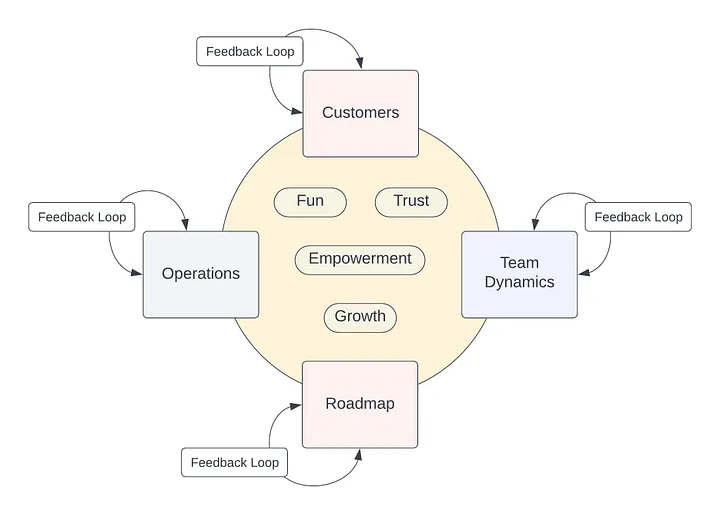

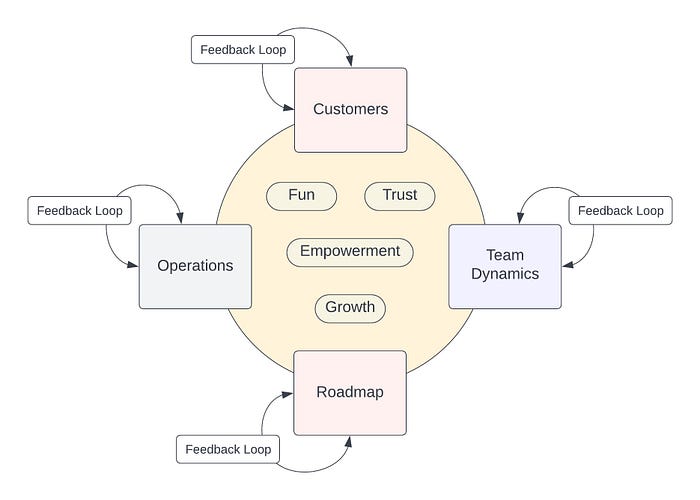

There is no one size fits all approach to tackling these challenges, however regardless of domain, there are universal aspects to a business which cover most your bases as a leader. I use the mnemonic FACTOR to make it easy to remember the dimensions. Feedback Loop-Attrition Plan-Customer Awareness-Team Dynamics-Operations-Roadmap. Focusing on these aspects have consistently held me in good stead, and helped rapidly shape engineering teams toward high performance.

It is key to understand that as your role evolves and you become more senior there are aspects that will change. Staying flexible to new expectations while looking for ways to scale your FACTORs is a way to maintain your growth as a leader.

1. Know Your Customers

In my first few days in a new area, I immerse myself in understanding who my stakeholders and customers are. What does success look like for them, and how the area I own can accelerate their success. For this, I leverage 1:1 conversations with stakeholders, their teams, and sometimes the leadership chain. I take a concentric approach, starting with the teams closest to me and branching outwards.

I keep a purely exploratory tone in these discussions, asking open ended questions and aiming to create a safe space for thoughts and ideas to flow. I try and seek examples to better understand, and repeat what I understood to remain on the same page. I express curiosity into their overall area of business, not just the parts that intersect with my team. I always close with “How can my team enable you to be successful?”. And I make darn sure I follow up with that. I’ve found this action bolsters trust and maximizes the chances of building upon a good foundational relationship.

After the initial meeting, I setup a recurring series with key stakeholders. My meeting schedule frequency is inversely proportional to the proximity of the team with mine. For ad-hoc syncs I leverage other asynchronous channels like email and slack, for more tactical and immediate things.

What do I do after each meeting?

I prioritize. Sometimes figuring out urgency is a project in on itself. I use my judgement and lean on my subject matter experts for context in assessing urgency. For non-urgent but important areas, I gauge if additional legwork is needed to gain clarity. I delegate these actions to my team as needed, and set expectations on timelines and follow up cadence. I leverage the async channels to keep my stakeholders apprised on progress, and use the recurring meetings to revisit topics and assess next steps.

What does this action do?

It fundamentally creates an awareness with my stakeholders and customers on who I am and the areas I own, and opens the door for other leaders to approach me. The awareness I create expands with each stakeholder I reach out to, and pretty soon I’ve established a core network.

Internally, it gives my leaders and my team a clear view of my priorities. It gives them opportunities to react and add to my perspectives, forming a complete picture and making them a part of the solution. It also gives my team opportunities to earn my trust by actioning on concern areas in a timely fashion.

Finally, it signals that I value stakeholder relationships, and sets an example to my team that they should too.

2. Know Your Operations

One of the most reliable ways to wrap your mind around your team’s business is to develop a first-hand understanding of the team’s state of operations. It gives you an unadulterated view of the state of the systems you own, and a window into what your customers experience while working with your product, and your team.

- Key metrics that indicate customer experience. These may be a combination of business metrics like rate of signups for your service, number of active users etc., as well as system metrics like availability, latency etc.

- Support Ticket metrics. Number of trouble tickets your customers and other teams submit to your team, average turn around time for your team to respond and resolve support tickets, your oldest tickets etc. They all give you a direct snapshot of customer happiness and your team’s ability to support your customers.

- Customer impacting events and corrective actions. Diving into past operational incidents like outages or bugs that resulted in negative customer impact, auditing corrective actions the team takes as follow-up and assessing the current risk of past impact vectors.

- Dogs Not Barking. These are silent, slow-burning problems, that may snowball into a catastrophe one day. A classic example is customer identifier with a limited schema that may one day get exhausted. This signal is a bit tricky to tease apart. For these, I leverage my team to brainstorm areas dogs may not be barking, and devise ways to monitor its progress, and a plan of action to mitigate & by when.

- Flat Spare Tires. As the name implies, these are systems that are seldom used but must work when you need it the most. Like backup systems. If your team does not have a good grip on these it could spell doom at the worst possible situation. Use the *Dogs Not Barking* brainstorm to also identify *Spare Tiers* that may be flat. Prioritize fixing these as you never know when you will need them.

I look for mechanisms for these areas. Does the team have a regular forum where ticket metrics get reviewed as a team and action items identified? Does the team have a clear prioritization framework to make room for the action items in the roadmap? Are there escalation processes for critical priorities? I don’t hesitate to step in and create mechanisms where they don’t exist, making sure I involve the team as it multiplies their buy-in.

3. Understand Team Dynamics

Besides stakeholder discussions, my first few weeks are spent having 1:1 conversations with everyone in the team. For larger teams I space these out and start with senior members. In my 1:1s I make sure I ask about who else I should be speaking with, and prioritize conversations with them. Similar to stakeholder conversations, I keep questions open ended and have genuine curiosity on what the other person is saying. This is as much a learning experience to the person I’m speaking to, as it is for me.

What do I walk away with after this exercise?

I sometimes walk away with confusing signals, and that’s ok. Humans are messy and our perceptions are not always binary or cogent. And certain signals need follow up conversations to become clear, especially ones unique to individuals. I pencil these in for follow up 1:1s with the person.

From my initial discussions, I try and identify macro themes that resonate with the team, as well as themes with discordant views. For instance, everyone might agree the software deployment process is long and tedious, but not everyone might see eye to eye on the approach to fix it.

What do I do with these signals?

There are a variety of things that can be done with these signals. But at its core, they offer me ways to figure out the tactical and strategic actions I can take when approaching team dynamics.

For instance, the tactical action might be to nominate a single threaded owner to solve the challenge of streamlining deployments. And the strategic action might be to instill a general practice of writing high quality designs when solving problems. Quality designs paint the team a holistic picture of the porblem with data, creating ways to harmonize discordant views; on say how to streamline deployments.

This style of 1:1s and the thought that goes after it, is a critical exercise early on. It creates a direct path toward creating connections and earning the team’s trust, as well as your ability to influence others in the long-term. I go through this exercise not only with my team but also with my upward leaders. As it gives me a crisp sense of leadership dynamics I should be aware of. The worst thing to do after this exercise is to do nothing. It is key to act on these signals to retain trust and ensure your ability to influence.

4. Establish your Roadmap

Your roadmap defines your reality. All projects small and large go in here. A project isn’t real unless it makes it into the roadmap. Refer to your roadmap when handling incoming work. Your first thought should be “I will slot this work in the roadmap after blah is done.”

What does a roadmap contain? Ultimately it is a living and breathing chronological listing of projects with timelines for each. Projects delivering in the next 90 days should have specific target dates for launch. Projects in the next 6 months should have the launch month, and ones farther out have the quarter it would launch in.

Advertising your roadmap is as important as having one in place. Your roadmap must be easily accessible to your team and your stakeholders. You’re successful here if your stakeholders refer to your roadmap proactively when approaching you with slotting new work. Refer to your roadmap when connecting desires to opportunities in career conversations with your team.

Remember your roadmap is not set in stone — just as how fluid your business is, so should be your roadmap. And your roadmap should be detailed enough to surface tensions. What projects will not launch on time if this new work has to be slotted in? Don’t be afraid to take a roadmap further into a resource plan — which is associating the number of people working on a project and modeling all assumptions.

Also remember your roadmap should transcend the tools you use to manage it. Tools will come and go, but your roadmap should not breakdown in the process. Whether you use Microsoft Projects, Jira, plain old excel or a simple text file — your roadmap should bring visibility into your plan in simple terms.

5. Create Feedback Loops

Feedback loops are an important guiding signal on the efficacy of something. The nature of feedback loops can vary from situation to situation, but it is essential to have some form of feedback loop for each aspect of your business. For instance, once a quarter I to send a note to all my stakeholders soliciting feedback on their experience working with my team. I encourage them to be transparent about all things big and small. I welcome them to share feedback about my own performance; either directly to me or with my leaders. Fascinatingly, after the first couple of times, stakeholders no longer wait for my quarterly emails to provide feedback.

With my team, I set an example with mechanisms. For instance, with each team activity, we reserve a way to solicit and reflect on feedback. Every team meeting has a segment where we reflect on what team activities are working for us, which ones need some TLC and which ones can we forgo and get back valuable time. When someone is stuck on a sprint task, they are encouraged to time-box their work and review progress with others. This creates channels of timely feedback and supports the engineer as they get unstuck.

I make it a point to revisit feedback topics during 1:1 interactions with my team as well as my stakeholders, creating multiple channels to share their thoughts.

What do I do with all this feedback?

Ultimately acting on the feedback loop is the #1 approach to making this exercise worthwhile and actually improving something. As with most things, staying mum on the feedback is the worst thing you can do as a leader. By engaging change, you project a sense of value to the feedback provider, encouraging them to be more forthcoming the next time.

The second most important thing is to approach feedback with an open mind by placing yourself in the feedback provider’s shoes. A closed mindset here is the undoing of this approach and your worst enemy. Instead embrace the feedback neutrally. Seek to understand the feedback better by exploring examples. Understand that lack of examples doesn’t invalidate the feedback. To the contrary, it means the onus is on you to give the feedback provider ways to engage when an example comes up.

6. Manage your Attrition

Attrition in any team brings a mixture of tangible and indirect impacts, some of which are felt much later especially if the attrition is a regretted — where the member opts to leave the team. On the other hand, un-regretted attritions — where a team member has to part ways due to performance concerns — when handled the right way, sets the bar for high performance in the team. Either way, as a leader you either have a hiring challenge or a retention challenge, and you need to have a plan for both.

I use my initial 1:1s with the team to assess job satisfaction and general happiness. Creating a safe space in the conversation helps get better quality signals in this regard. I then check if folks have a career progression plan established and how well they’re tracking toward the plan. I follow up if there are other aspects unique to the person that’s driving dissatisfaction.

My follow up 1:1 usually start with this topic. Failing to address the topic head-on doesn’t make it go away. To the contrary, it creates blind spots and missed opportunities to address potentially systemic problems. I brainstorm together on ways to grow them out of the problem, and seek to develop a common understanding. My role in the brainstorming is to walk the person through aspects of the dissatisfaction and connect them to potential opportunities to overcome their challenge.

A strategy to stay ahead of the impact of attrition in general is to maintain a steady pipeline of potential candidates. While you as a leader should do everything in your power to mitigate attrition, a steady hiring cadence ensures the risk to your team’s rhythm and ultimately to your business‘ growth has a mitigation plan. Remember, it is too late if you start hiring after a person leaves as you create a gap in velocity that you don’t have a plan to cover. At worst this adds pressure to the rest of your team to absorb the impact, leading to further dissatisfaction.

7. Have Fun!

It should be fun to build things together as a team. If it’s not, you as a leader are responsible for creating a fun environment. I make sure to keep an ear out to the team on what fun means to them, and connect relevant opportunities to have fun. I’m self aware that _creating_ fun activities is not my forte but I enjoy _partaking_ in them. This helps me ensure either there is a team mechanism to self organize fun activities, and in the abence of one ensure I am making time to organize them — even though it isn’t my forte.

Comments ...

No Comments Yet ...Add One